Blog

The Infrastructure Institute blog features reflections from staff and guest contributors that explore various elements of global urban infrastructure.

LX Factory: An Example of What Adaptive Reuse Can Offer Cities

By Eva Hellreich

January 2026

Stepping through the archway into LX Factory, you’re immediately confronted with variety. A mobile florist is parked beside an open-concept restaurant, facing a shop selling ceramics, handmade clothing, and prints by local artists. Despite sitting beneath a bridge and deep within the city of Lisbon, the space feels calm and unhurried. People linger over coffee, chatting in multiple languages in front of steel-framed windows that carry the marks of the former factory.

LX Factory occupies roughly 247,500 square feet in Lisbon’s Alcântara neighbourhood. The site began life in 1846 as a textile factory established by the Companhia de Fiação e Tecidos Lisbonense (the Lisbon Spinning and Weaving Company). Over the next century, the factory was home to food processing, printing, and other industrial uses, making the complex a central part of Lisbon’s manufacturing economy. As industrial production declined in the late twentieth century, the site gradually emptied. By the 1990s, it sat largely vacant until its sale in 2007 created an opportunity for reinvention.

The long-vacant factory complex was acquired by Portuguese real estate firm MainSide Investments in 2007, which led its transformation into LX Factory as a creative, mixed-use hub through a light-touch approach that preserved the site’s industrial character. Ownership later changed again, including a 2017 acquisition by France-based Keys Asset Management, with subsequent stewards maintaining the site’s core adaptive reuse model. The transformation of the site in the mid-2000s is a good example of adaptive reuse. Rather than erasing the past, the project repurposed existing buildings for new functions while retaining their architectural and historical character. Adaptive reuse has become an increasingly important approach in sustainable urban development, conserving materials, reducing demolition waste, and preserving cultural heritage while allowing older buildings to meet contemporary needs. In this sense, the existing building is treated not as a constraint, but as a foundation for new possibilities.

At LX Factory, this approach meant preserving the industrial structure of the brick-and-steel complex while introducing a wide mix of uses, including offices, artist studios, cafés, restaurants, design workshops, outdoor space, and cultural spaces. Change happened without sweeping redevelopment. Designers worked with the textures and forms already present, allowing the site’s material history to remain visible. The result feels both contemporary and rooted in memory.

On Sundays, the courtyard and corridors take on the qualities of a public square. Families wander between market stalls, artists talk about their craft with visitors, and musicians prepare to play beneath murals adorning the centuries-old walls. The pace encourages people to stay rather than pass through. Commercial activity blends with informal social life, creating encounters that feel spontaneous rather than scripted. This recurring social use is central to placemaking and helps explain why adaptive reuse projects often generate civic value beyond their economic function.

LX Factory naturally invites comparison with places such as Toronto’s Distillery District. Both sites preserved industrial buildings and introduced cultural and creative uses that have become defining urban destinations. In each case, historic architecture supports a rhythm that accommodates weekday work and weekend leisure, showing how industrial heritage can remain active within a city’s contemporary social and economic life. Yet the differences between these sites are just as instructive. Growing up in Toronto and attending high school near the Distillery District, I spent time in its walkways and cafés while being acutely aware of its limits. A coffee purchase only allows so much time in a district that feels increasingly curated and consumption-driven. At LX Factory, the atmosphere felt slower and more porous. While it attracts visitors, it does not feel organized primarily around tourism, and people appear comfortable lingering without pressure to spend.

For cities like Toronto, the lessons are less about replication than about approach. Across Canadian urban regions, underused warehouses, former industrial corridors, and aging employment lands are often seen as opportunities for redevelopment. LX Factory suggests the value of working incrementally, allowing mixed and temporary uses to take root, and recognizing social life as a legitimate outcome of planning and design. In this context, “meanwhile” uses are not simply placeholders, but active contributors to urban vitality.

Context matters, of course. Lisbon’s regulatory environment, land markets, and cultural heritage frameworks differ from Toronto’s, and any similar effort would require adaptation rather than imitation. Still, the underlying principles remain relevant. Thoughtful reuse, flexibility over time, and respect for existing urban fabric can support places that are economically viable while remaining socially generous. LX Factory demonstrates that older buildings can continue to work for cities when they are reimagined with care. Through adaptive reuse, architecture becomes a way of understanding where a city has come from, while shaping how people experience it today.

For a deeper look at how aesthetics shape how we engage with public and urban spaces, tune in to the Good for Cities episode “Are Beautiful Buildings Good for Cities?”

About the author:

Eva Hellreich is the communications officer for the Infrastructure Institute. Their work in non-profit arts has heavily influenced how they think about and advocate for space and entry points to civic engagement. Outside of work, they enjoy being active in their YIMBY neighbourhood association, spending time outdoors and cooking for their dog.

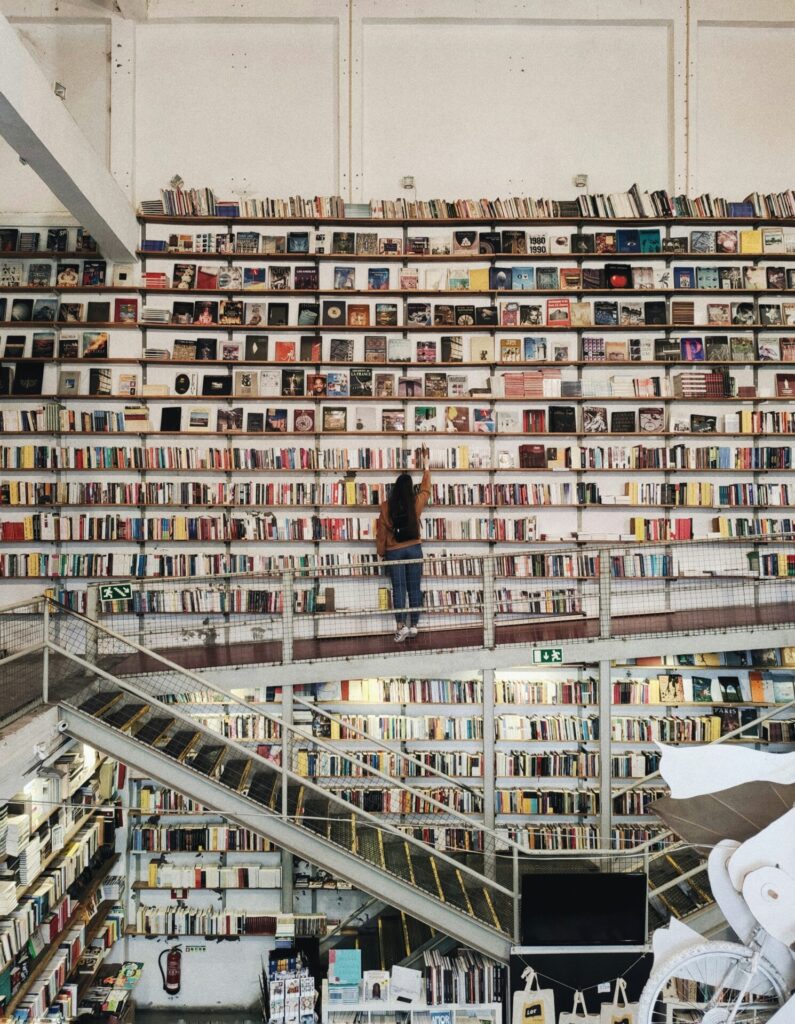

Pictured above: inside the Ler Devagar bookstore, home to a three-story press and secret record shop as well as contemporary and classic literature in various languages.

Photo credit: Vita Maksymets on Unsplash.

Pictured above: the laneway between various shops and seating at LX Factory.

Photo credit: Photo by Maxence Bouniort on Unsplash.